Introduction to the Japanese Reading and Writing System

Published on June 18 2016

Segment: tips

Hello, and welcome to the first of many tutorials offered by Japanoblog. This first tutorial is a general overview of the 3 different types of writing systems used by the Japanese: hiragana, katakana, and kanji - each of which will be covered in associated tutorials of their own.

So, without further ado, let's get started!

Why use 3 writing systems?

Each version of the writing system, which can be used by themselves, or all integrated into a single sentence (see below), has its own reason.

私はテレビを見ています。

Hiragana is used for Japanese-specific words, grammar, phrases, and/or particles; usually written with smoother, rounder symbols.

Katakana is used for foreign words (as in, words that are borrowed from other languages that aren't native to Japan, like "Banana"); usually written with more ridged symbols

Kanji is actually a borrowed system from Chinese, but is used to represent a shorthand version of words, and can represent different things based on the context; usually contains complex symbols consisting anywhere from 1 to 20+ strokes to complete.

The Japanese language (all forms) are usually made up sound bites, which is why it's called a Phonetic system. Whereas English words and sentences can have multiple sounds (and silent letters [subtle, debt, opossum], and words that break the "common rules" ["i before e" rule, such as sufficient, veil, receipt], words that are pronounced differently based on the context [read, live, wind, bow], and abbreviations [Mr, Mrs, etc, St, Ave], and...a bunch of other stuff), the Japanese system consists about 46 sounds, including the vowels, so no matter which system is being written or spoken, the words, sentences, and phrases are a combination of those ~46 sounds, creating a 5x10 chart often called a gojūon, which makes it easier to learn. (There are 3 obsolete characters from older systems, which makes a total of 49, not including variations, which will be explained later.)

Overall, there are 5 vowels, 43 consonant-vowel combinations, and 1 singular consonant.

The basics revolve around the vowels:

a - pronounced like "ah"

i - pronounced like "ee"

u - pronounced like "ooo"

e - pronounced like "eh"

o - pronounced like "oh"

The hiragana and katakana (often called "kana" together) systems follow the same pattern: starting with the vowels, the consonants are prepended for each, creating a handy learning chart (see the hiragana and katakana articles) and creating the sounds for each symbol, such as k, s, t, n, h, m, y, r, and w (and finally the letter "n").

Hiragana - in a nutshell

Hiragana (pronounced "hee-ra-ga-na") is Japan's native writing language. While it may looks fairly pretty with a bunch of smooth characters, there are some very subtle differences, such as how P, R, and B look similar in English.

Hiragana (pronounced "hee-ra-ga-na") is Japan's native writing language. While it may looks fairly pretty with a bunch of smooth characters, there are some very subtle differences, such as how P, R, and B look similar in English.さ (sa) and ち (chi) are basically the same symbol, but backwards. は (ha), ま (ma), ほ (ho), and も (mo) look fairly similar as well. Lastly, ろ (ro), る (ru), and ら (ra) all have similar traits as well.

Hiragana can be used by itself, or with a combination of Kanji (see below) to form sentences, words, or phrases. For example, "はじめまして" (pronounced "ha-ji-me-ma-shi-te") is a very common phrase used in introductions, meaning "How do you do?/I am glad to meet you." On the other hand, "食べます" (pronounced "ta-be-ma-su", means "to eat") turns the first character into Kanji, and the rest stays in Hiragana form.

Katakana - in a nutshell

Katakana is much simpler than Hiragana, as it isn't usually combined with Kanji or is used by itself in phrases. Katakana is mainly used to identify items that are not native to Japan, such as Hamburgers, Bananas, or even E-mail (yes, Email was invented in America), which are often called loan words.

Katakana is much simpler than Hiragana, as it isn't usually combined with Kanji or is used by itself in phrases. Katakana is mainly used to identify items that are not native to Japan, such as Hamburgers, Bananas, or even E-mail (yes, Email was invented in America), which are often called loan words.The symbols in Katakana use the exact same pronunciation chart as Hiragana, so it is made up of the same sounds (which makes it easier). However, the symbols can be fairly similar to Hiragana or drastically different - some even double as Kanji. The symbols are more rigid and jagged than Hiragana, so it may seem odd to recognize them, but they are very different from Hiragana. The only symbol that Katakana has that Hiragana doesn't have is a long sound (ー), which literally looks like a dash, but carries the voweled sound from the previous symbol over.

The good thing is that most of the words that are in Katakana are fairly recognizable. Guess what these are: バナナ (ba-na-na), ハンバーガー (ha-n-ba-a-ga-a), and コーヒー (co-o-he-e).

The answers are: banana, hamburger, and coffee. In the example sentence used above, the item in the middle is written in Katakana: テレビ (pronounced "te-re-bi"), which translates to "television".

And no, you can't just "Japanize" American words to make them "Katakana-ed", like many people try to do with Spanish by just adding a "o" to the end of the word. It doesn't work like that; some words are loaned from other languages, like German, Polish, and Thai, and may not be easily translatable if you don't know their meaning, such as ローソク (ro-o-so-ku, meaning "candle").

The Variations

Along with the standard ~46 sounds that make up the Japanese language, some of the sounds can have modifiers, called Dakuten, or voicing marks. Most people may have already seen these, like trying to find the pronunciation of a certain word (for example: the English pronunciation of "Japanese" is \ˌja-pə-ˈnēz, -ˈnēs\). However, in Japanese, there are 2 main ones: a small set of two dashes (゛), and a small circle (゜). These two symbols, when added to certain series of symbols, slightly changes their sound. The K's turn to G's (for example: か [ka] + ゛ = が [ga]), the S's turn to Z's, the T's turn to D's, and the H's turn to B's. The only modification the small circle makes is on the H set, turning the H's to P's.

These same sets can also have small versions of Y symbols added, like きゃ, きゅ, and きょ, turning the same set of sounds into a slurred "_ya" sound. For example: "Tokyo" is fairly easy to say, but it is written (in Hiragana) like this: とうきょう (to-u-kyo-u, not pronounced "toe-key-yo").

But what if something is being quoted?

Unlike the double quotation marks (") that most languages use to identify when a phrase is being said, the Japanese system uses corner brackets (「」) to identify a quote, so there shouldn't be a mix up.

Kanji, in simple terms

A whole series of articles could be written on Kanji, but I will say this: Kanji is the answer when words need to be used. Put it this way: if the whole Japanese written language was written in nothing but pure Hiragana and Katakana, the printed media would easily twice, if not three times, the size. Just imagine having to spell out each sound that was made when writing a word, instead of just writing the word itself?

A whole series of articles could be written on Kanji, but I will say this: Kanji is the answer when words need to be used. Put it this way: if the whole Japanese written language was written in nothing but pure Hiragana and Katakana, the printed media would easily twice, if not three times, the size. Just imagine having to spell out each sound that was made when writing a word, instead of just writing the word itself?Okay, that's a bit confusing. How about this: instead of "Theme Park", it had to be written "Tha eem mm paar urk" - that's fairly hard to write, much less harder to read.

Kanji, which is a (borrowed) system from the Chinese, uses a combination of radicals and other strokes to create shortened version of full words, and can represent something just by the symbol, instead of the Hiragana (Katakana doesn't usually have a Kanji counterpart). If the symbol "ひ" (hi) was seen, it could mean anything; the sun, light, cost, fire, princess, or even a spleen. However, if 日 was used instead, then it's easier to identify what it means (it means "Sun"). The same thing could be said in English if you were to see the word "live" - does that mean "living", or "a live event"?

Unlike the Kana systems that only have about ~46 sounds (plus their variations), there are over 3000 Kanji and counting! Students learn about 1000 of these while in elementary school, then another 1130 while in middle and high school! (And I barely know 20 after 4 years of Japanese...)

When reading Kanji, it is common to come upon an unknown Kanji, in which case you can either ask what it means, or figure it out from the context - just like seeing a word you aren't familiar with, but without the benefit of being able to "sound it out".

While the majority of Japanese know many of these Kanji, the older generation knows a lot more, which easily bypass the 3000 mentioned before. There's actually a funny phrase that relates to this:

"A Chinese man can read a Japanese newspaper,Kind of funny, don't you think?

but a Japanese man cannot read a Chinese one."

Is that it?

Oh no - the English language is sprinkled into the modern Japanese culture as well. Many English phrases are used on advertisements, communication, TV shows, and more - just because it's part of whatever is being referenced.

Oh no - the English language is sprinkled into the modern Japanese culture as well. Many English phrases are used on advertisements, communication, TV shows, and more - just because it's part of whatever is being referenced.Aside from English itself, the English equivalent of Japanese (as in, the way that Japanese is written so those that don't speak it, can) is Romanji, which is the breakdown of the sounds in the Japanese language. For example, the sentence that we used above (私はテレビを見ています。) would be written in Romanji like this: "Watashi wa terebi o miteimasu."

Anything else?

Actually, yeah. While English is usually written left-to-right, and sometimes vertically, the Japanese system can easily be written in the same way - with one modification.

Actually, yeah. While English is usually written left-to-right, and sometimes vertically, the Japanese system can easily be written in the same way - with one modification.If written left-to-right, then it is usually read from top-to-bottom. However, if written from top-to-bottom (as in, vertically), then it is read right-to-left. Yeah, so it just got more complicated.

In summary

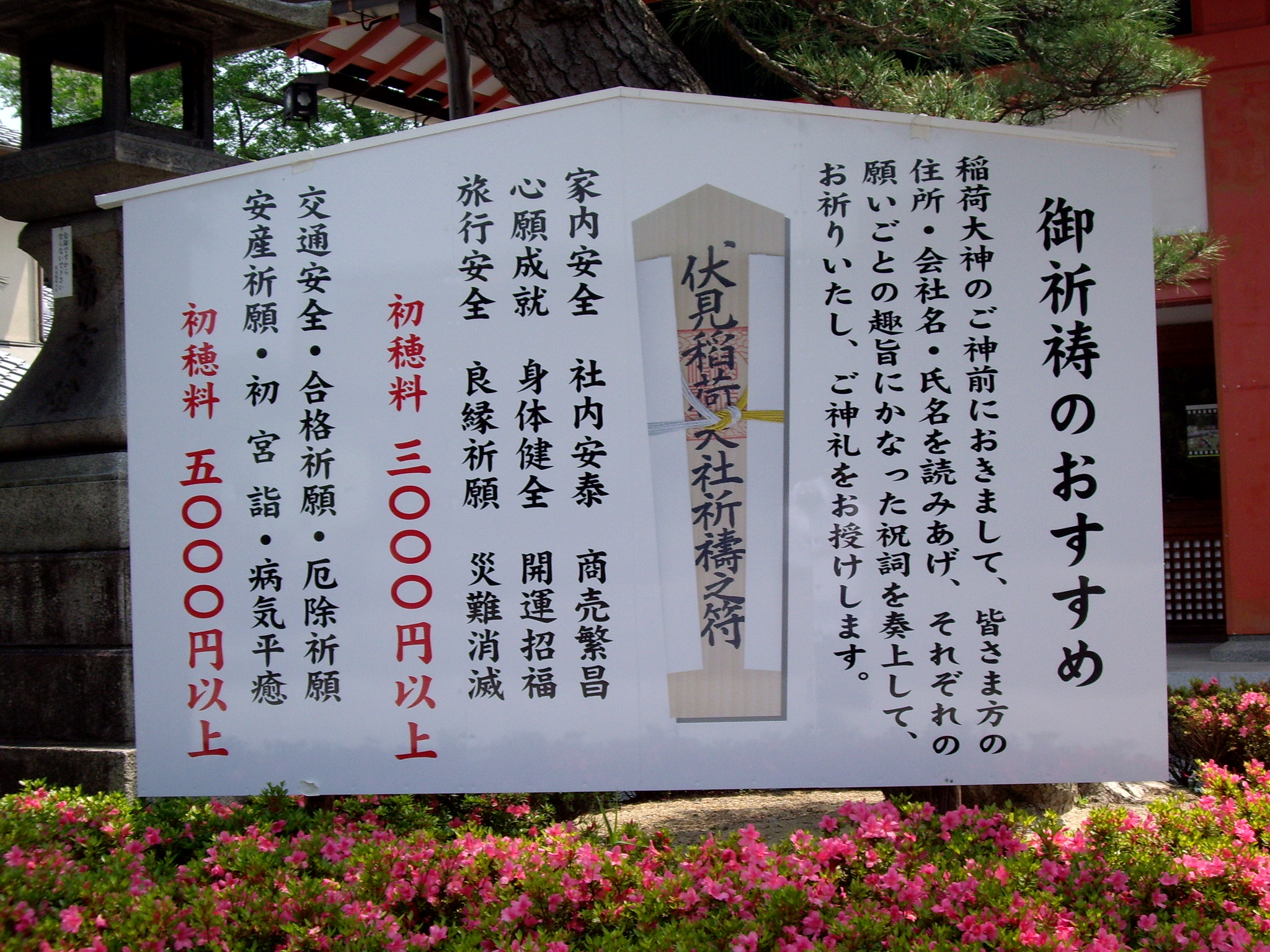

The Japanese writing and reading system is fairly complex, but so is English when you break it down to its basic rules. Each writing system has its own reason for existing, just like certain SAT words need to be learned. At any one time, any or all of these systems can be used at once, and if you don't know what you're looking at, you can easily walk into something unwelcome (出口 means "Exit").

The Japanese writing and reading system is fairly complex, but so is English when you break it down to its basic rules. Each writing system has its own reason for existing, just like certain SAT words need to be learned. At any one time, any or all of these systems can be used at once, and if you don't know what you're looking at, you can easily walk into something unwelcome (出口 means "Exit").While Hiragana may look pretty, Katakana may look harsh, and Kanji just looks confusing, all of these writing systems can be understood when studied, but it's fairly hard to know what they represent without either practicing or being immersed in the language. And don't even get me started on grammar - that's a whole different can of worms!